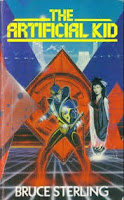

Science fiction is often unfairly unburdened with the expectation of predicting the future when in fact the majority of sf is just trying to tell a story that uses what’s known in the present to extrapolate upon a future or alternate setting. Science fiction is not in the business of futurism. Yet still, a number of books and stories have described situations or scenarios which have become reality. The usage of technology for the public broadcast of personal life is where Bruce Sterling’s The Artificial Kid (1980) accidentally, or at least partially so, becomes a prophet.

In the future, humanity has spread across on the universe, and on the planet Reverie it has created for itself a future, hyper-corporate, neo-Victorian version of itself. Twirling nunchukkas through the streets of its largest city is the Artificial Kid. A reality tv star with waves of fans, the Kid is surgically altered in ways today’s plastic surgeons may dream of but don’t yet have the technology for (plastic hair, faux-skin, muscle healers and the like), all in support of his combat lifestyle. A mini-swarm of drone cameras following him wherever he goes, the Kid films his encounters with a rival gang, then edits the material later to be published and sold to his fans. It’s during one of these encounters with the gang that things get out of hand, and the Kid finds himself outside, far outside his comfort zone.

The overall swish and curl of The Artificial Kid is of a dog looking to lay down. Turning in a few circles before settling in, the novel takes its time deciding what it wants to do with itself. Sterling introducing its concepts, then more, then even more, until finally, at some point, the underlying purpose and direction of the Artificial Kid’s story emerges. Thus, for readers who look to sf for its ideas and sensawunda, there is the potential the novel tickles your sweet spot. Clicking with today’s society and technology, the Artificial Kid would certainly be something of a street MMA influencer. On the other hand, readers who enjoy rich plot and character may find themselves constantly missing something—loosely engaged by the singularity of the ideas, but not tightly embedded in the Artificial Kid’s plight.

But it is in the plight that the reader finds the novel’s substance. Sterling juxtaposes the Kid’s environs as they transition over the course of the novel to lay the main of the message. To say exactly what that is would spoil the novel to some degree. Suffice to say, what the Kid once thought of as normal takes on a new light while taking his “hero’s journey”, just as Sterling reinforces the value of the real world. Cyber-, bio-, and perhaps other forms of punk playing their roles, the Kid at the end is not the same as the Kid at the beginning, even if Sterling’s cues are indirect.

One interesting aspect of The Artificial Kid is that it is a novel, as of 2020-ish, which has not seemed to have aged four decades. Where the writings of Heinlein, Asimov, and others wear their years on their lapels, Sterling’s novel possesses ingredients and a style that is not out of place today. From the presence of social media to people of varied race and sexual orientation, the post-human elements to the affected dialogue, if anything Sterling was able to transcend his era with the novel.

Sterling never uses the word ‘selfie’, but throughout The Artificial Kid it’s right there on the tip of his fictional tongue. Just as recognizable are the plastic surgeries the Kid has undergone and the pressure he places upon himself to uphold certain standards of beauty and behavior for the public eye (Instagram “stars” come to mind?). Social media before it the term was a thing, the only thing Sterling adds is a degree of violence akin to classic street brawls—something we see being fought less glamorously today with guns. Regardless, it’s only a matter of time before the real world has a figure like the Kid, paparazzi replaced by drone swarms, and a Youtube channel with millions subscribers.

Whether or not the read will appreciate Sterling’s style is another thing. The dialogue affected (in a quasi-Shakespearian, semi-antiquated style), the reader’s appreciation of the novel will partially hinge on their appreciation of the characters speaking to one another. The gang showdowns, for example, sound a little like Capulets and Montagues. But as the novel evolves, this type of dialogue fades—still slightly stilted but tough to discern between something intentional or accidental.

Like many if not most of Bruce Sterling’s novels, The Artificial Kid is more a presentation and interaction of ideas than it is a traditional intro-body-climax-resolution type of story. Sterling hedging his bets on readers’ engagement with his imagination for future societies, tech, and politics, more so than plot, character, and dialogue, the novel tries to grab the reader with a post-human milieu that has a social media, ninja warrior with plastic hair at the forefront. Love him, hate him, follow him, he’s the Artificial Kid. But interestingly, the moral of Sterling’s book is something more organic…

No comments:

Post a Comment