People much more famous than me have stated that the internet is the democratization of worldviews. What I take this to mean is that popular opinion holds sway. How much? Hard to say. But what can be said with certainty is that the voice of critics with the clout to proclaim acclaim has dwindled in power due to the internet. Anybody with a youtube account or Reddit login can be a critic these days and get as many if not more eyes. I lament that much of this content, if not the majority of it, does not have the background, experience, or objective mindset that being a book critic requires. The bell curve of quality has been flattened.

Thursday, October 31, 2024

“Critically Acclaimed”: What a Difference a Couple Decades Makes

Review of Polostan by Neal Stephenson

Where the Baroque Cycle looked into the dawn of the enlightenment, Newtonian physics, early computing, and the birth of the stock market, Polostan digs into primitive nuclear physics, early communism, and global 1930s industrialization. Stephenson happily wallows in this historical period through the bright eyes of a young woman caught between East and West named Dawn/Avrora (depending which hemisphere she is in). Though born Avrora in the wild steppe of Russia in the early 20th century, as a child she ends up as Dawn in the wild west of the US after her mother runs away from Stalin's brand of utopia to start a new life. A rough life, Dawn has many an adventure in Montana, in the labor strikes of Washington D.C., in the Chicago World's Fair, and in the backwoods of the midwest after getting caught by a gang of rednecks who care more for her paycheck than her wellbeing. But it's physics, particularly nuclear physics, which Dawn's life seems to return to time and again. Capitalists pulling her one way and communists the other, Dawn must eventually decide how to best play one side against the other.

Monday, October 28, 2024

Review of The Mercy of Gods by James S.A. Corey

The Mercy of Gods begins on Azean. An extra-terrestrial planet, humanity has nevertheless terraformed it by finding ways of conflating local gene structures with the plants and animals that humans require to exist. The story follows the crack team of researchers who accomplished this major gene-splicing feat. A (figurative and literal) alarm goes off when one of the researchers discovers an anomaly in their work that can only be extra-extraterrestrial—truly alien in nature. It isn't long after the Carryx and their slave species invade Azean and take humanity captive. The research team's adaptation, or not, to captivity is the story that follows.

Wednesday, October 23, 2024

Review of White Light by Rudy Rucker

White Light tells the anything-but-mundane story of mathematics professor Felix Rayman. Facing a dead-end job and marriage headed to divorce, Rayman attempts to spice things up by trying lucid dreaming. Though successful, his sense of reality begins to slip. When he should be preparing a lecture, visions appear. While he's trying to research Cantor's continuum hypothesis, gods and devils do, too. Rayman eventually calls upon Jesus for help, and is promptly tasked with taking a ghost named Kathy to Cimon, which is a place/existence permeated with the forms of infinity. Oh, Rayman fulfills Jesus' task. But that is just the tip of the boot that kicks the reader in the ass, sending them into the bizarreness of Cimon. Don't hang on for the ride; spread your wings and soar.

Sunday, October 20, 2024

The Salmon Who Dared to Leap Higher by Ahn Do-hyun

I don't often do this on Speculiction. In fact, I'm not sure I've ever done it. I'm going to in essence write two reviews. The reason is, I'm not sure if Ahn Do-hyun's The Salmon Who Dared to Leap Higher (2024) is a book for children or for adults. The distinction is critical, and I'll start with the positive.

If The Salmon Who Dared to Leap Higher is a book for children, then I can wholeheartedly recommend it. Though it is (awkwardly) framed by an adult trying to deal with feedback to something they have created, it quickly switches into the life cycle story of a salmon. It tells of a young, unnamed silver salmon who is learning about life in the ocean. He meets other salmon in his shoal, falls in love, and eventually makes the freshwater trek upriver to the shoal's spawning grounds. This journey is peppered with metaphors and allegories that link the salmon's circumstances to the basics of human life—growing up, starting a family, making difficult decisions, trying to find your way in a group, etc. It's presented with a strong degree of simplicity so that even the 'birds and the bees' have an aura of innocence. Though the title is a spoiler for the climactic moment, most kids won't connect the dots. <smile> In terms of delivering perennial philosophy on the basic building blocks of human existence, social to biological, this short book covers it in sweet, charming fashion for kids.

Tuesday, October 8, 2024

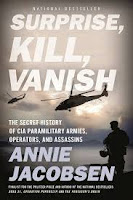

Review of Surprise, Kill, Vanish: : The Secret History of CIA Paramilitary Armies, Operators, and Assassins by Annie Jacobsen

We all have them; Youtube holes we fall into when we shouldn't. One of mine is covert operations—the world of secretly gaining information, agent handling, and, when “needed”, clandestine action—the James Bond stuff of the real world. The Spy and the Traitor by Ben Macintyre is a great example of such history, and so it was with gusto I dove into Annie Jacobsen's Surprise, Kill, Vanish: : The Secret History of CIA Paramilitary Armies, Operators, and Assassins (2019).

Suprise, Kill, Vanish is a combination of content. A historical overview, the book is structured to cover the phases of the CIA's existence. Jacobsen highlights the changes in president, American culture, presidential policy, and world events which directed the moral compass of the CIA, from underhanded to overhanded, justified to quasi-justified, and its growth, development, and evolution as an organization. From its inception in WWII to its iteration under Barrack Obama, that's the period the book covers.

Thursday, October 3, 2024

Review of The Chalk Giants by Keith Roberts

Why exactly The Chalk Giants is an odd duck starts with the wikipedia quote describing what the book is: 'a linked collection of short stories'. Is it a collection or novel? I would argue it's a loose concept album. The songs are individual pieces of music, but they fit a broader motif.

The first story, “The Sun Over a Low Hill”, describes Stan Pott's frantic escape from a city under curfew circa the mid-1900s. Draconian control measures in place, Potts escapes near apocalyptic urban conditions. Smashing through barriers, he drives a car stuffed with supplies to a lonely house by the sea which houses a small group of people. Throughout this escape Potts' strained sense of identity has a definitive Weirdness to it, in turn leading down dark psychological roads and to even darker decisions. “Fragments” is set at the same lonely house, but tells the story from the other characters' points of view. The Weirdness only gets Weirder, but doesn't lose its humanity.

Review of The Solar War by John French

As a novel, The Solar War is what's written on the tin. A massive, end-to-end battle stretching the length of the solar system. Rogal Dorn sets the defenses, while the White Scars stand by, at the ready. And Peturabo does not disappoint, attacking Pluto with his Iron Warriors. Together with remnants of the Sons of Horus, they start pushing Sol-ward. With echoes of Horus Rising, Garviel Loken and a Remembrancer get caught in the battle. Witness to unearthly events, the battle for Terra will prove to be more than Space Marine vs. Space Marine.