Thursday, February 18, 2016

Speculiction on two-week vacation...

To you, the faithful thimbleful who regularly visit my blog, I will be away for two weeks in Thailand. Those things resembling reviews will re-commence when I return, and perhaps a few photos of the country...

Review of At the Mouth of the River of Bees by Kij Johnson

Encountering

Kij Johnson’s short fiction as it pops up in a year’s best or in the random

anthology, here in a magazine and there on Clarkesworld, one never knows which

face will appear. One sharply literary,

the associated works have abstract poetic dimensions that dissolve into images

and ideas connecting in the mind even if they seem to defy comprehension on

paper. The other face is one more

traditional and charming; a classic storyteller cognizant of tone resides

within Johnson. Poetic and charming a

vibrant pair of ideas in themselves, her 2012 collection At the Mouth of the River of Bees (2012) exemplifies these

qualities, and as I was to discover, additional faces.

Johnson’s

poetic face is best captured in the story opening the collection, “26 Monkeys,

and the Abyss.” Lurking behind an obtuse

little tale of a woman who buys into a traveling monkey show are the personal issues

she is dealing with in real life, just visible off-screen. Showcasing the fact genre authors can indeed

produce quality, literary material, spec fic at short length hasn’t come much

better. “Story Kit” adheres more literally

to the title than one might expect.

Opening with Damon Knight’s six story types, Johnson examines, in

prosaic fashion, the elements that go into writing via references to Greek

tragedy and contemporary, though unnamed, fiction. Seeming to evolve into a narrative more

personal than universal, the (meta-) story can also be read as a feminist text

for Johnson’s goals and struggles with pen in hand. A post-modern, abstract gem, it will not be

enjoyed by all precisely for those reasons.

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

Review of A Man Lies Dreaming by Lavie Tidhar

Reading

the premise of Lavie Tidhar’s 2014 A Man

Lies Dreaming, several questions immediately popped into mind. Didn’t Tidhar already play literary games

with a pulp private eye in Osama? Is he just hoping to cash in again on the

same idea? Moreover, didn’t Norman Spinrad already write an alternate history

wherein Hitler was a pulp writer in The Iron Dream? And didn’t Brian Aldiss already have a discussion with Hitler

in London in “Swastika!”? Is Tidhar’s

novel really going to be such an original work?

I’ve

since finished the novel, and my answers to those questions are… ambiguous. Indeed both Spinrad and Tidhar’s novels are alternate histories wherein Hitler

never had the chance to form the Nazi party or take power in Germany, and

instead became involved in pulp fiction.

But where Hitler was the writer of pulp fiction in The Iron Dream, he is a character in pulp fiction in A Man Lies Dreaming. Wish fulfillment, in other words, is in the

hands of the fictional author in Spinrad’s novel, and in the hands of the real

author in Tidhar’s. Headed in different

directions, Spinrad achieves historical and social commentary while Tidhar gets

revenge on one of the most infamous historical figures known (yes, in the same

vein as Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious

Basterds).

Sunday, February 14, 2016

Review of Under Heaven by Guy Gavriel Kay

I

have come to realize Guy Gavriel Kay is the sneakiest, sliest, deadliest writer

of fantasy on the market today. Oily

smooth prose the primary weapon, he tells fascinating mytho-operatic tales from

ages past. The dagger of bittersweet

drama his killing blow, the reader is entranced before they have a chance to

realize their politically correct toes have been stepped on. Silently from the shadows, 2011’s Under Heaven displays the fine degree to

which Kay has perfected the art of killing.

Like

the majority of Kay’s fiction, Under

Heaven uses the details of real-world history as its backdrop. Changing the names to protect the innocent, Under Heaven uses Tang Dynasty China,

particularly the An-Shi Rebellion, rendered as the Kitai and An-Li Rebellion

respectively, as its story analog. An

event that overturned the greatest civilization the world had seen, the drama

started at the top and affected everyone to the bottom, millions uprooted or

killed, including the emperor. Under Heaven, while skipping the bottom,

contains all of the tragedy and drama of the Rebellion’s unraveling in tragic,

fantastical form.

Friday, February 12, 2016

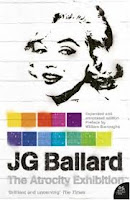

Review of The Atrocity Exhibition by J.G. Ballard

Pablo

Picasso had his “blue period,” Max Ernst his “American years,” and Georgia

O’Keeffe her later “door-in-adobe” phase.

For J.G. Ballard, the early part of his career could be called his

“psychological catastrophe years.” Using

environmental disaster as a doorway to viewing minds under duress, novels like The Drowned World, The Drought, and The Crystal World unpacked the underlying subject matter. For the next phase of his career, Ballard

moved into the world of celebrity, media, violence, sexuality, and how they

distort and are distorted by reality.

Like any good artist, Ballard produced preliminary sketches prior to

delving into the longer length works of Crash,

Concrete Island, and High-Rise. Arguably as experimental as literature can

be, this initial feeling-out of mass media’s effect on the individual is 1970’s

The Atrocity Exhibition.

A

collage of Marilyn Monroe, fast cars, Vietnam War imagery, pornography, and

numerous other symbols of the 60s shredded into bits and pasted randomly back

together, The Atrocity Exhibition is

as much art as literature. Presentation literally mimicking a gallery

exhibition (i.e. the ability to walk in and let your gaze fall where it will),

readers looking for traditional storytelling should run. Like a later novel The Unlimited Dream Company, Ballard presents the same variety of

images, symbols, and conceptions from different angles, forcing the reader to

take a step back to view the larger whole.

There are thus recurring characters, but it is not their story, rather

the multi-perspective view to their experiences which address Ballard’s

concerns.

Wednesday, February 10, 2016

Review of The Machine in Shaft Ten and Other Stories by M. John Harrison

The

more of M. John Harrison I read, the more I begin to believe he emerged from

the chrysalis fully fledged. Even his

first published stories display a maturity, a poise that the majority of

writers seek but can never find. That

emergence is captured in Machine in Shaft

Ten and Other Stories (1975). Like

an artist’s preliminary sketches, many of the stories would later be developed

into Harrison’s novel length work, notably the Viriconium sequence and The

Centauri Device. Bleak visions

tattooed onto vivid wastelands and fantastical landscapes, Harrison’s awareness

of the written word is bar none.

The

collection opens with its most incongruous tale, the eponymous “Machine in

Shaft Ten.” In fact a Jerry Cornelius story that (intentionally and perfectly)

smacks of Moorcock’s style, which in turn smacks of the classic British

gentleman story caught up in events over his head, it looks into a giant

emotion converter discovered at the Earth’s core. The second story, “The Lamia and Lord

Cromis,” is likewise classic, but only in feel.

One of the most dynamically realized settings in the collection, it

tells of the sword-and-sorcery anti-hero, Lord Cromis “who imagined himself to be a better poet than a swordsman” as he

hunts a beast through wilds of Viriconium with the dwarf Rotgob. The final showdown is the opposite of classic

but fitting.

Review of The Drawing of the Dark by Tim Powers

Tim

Powers is one of the most original and wide-ranging fantasy authors on the

market. Unlike such writers as M. John Harrison, Ian McDonald, Elizabeth Hand,

or Jeffrey Ford, however, he did not emerge on the scene fully fledged. It took a few books for Powers

to find his form and voice and integrate them with the ideas

floating around in his head. While

singular, Powers’ third novel, The

Drawing of the Dark (1979), remains part of this transition. Pace and action are brisk and the scenes vivid, but the prose is as loose as the coherency of the overall story—a

lot of rollicking fun, but very superficial (much like chunks of Roger Zelazny's oeuvre).

Working

with Eur-asian history, Powers sets 16th century East and against West in a

battle of the supernatural.

Sword-for-hire Brian Duffy the hero of the day, things start simply,

even realistically for him: he’s given a bag of gold ducats for taking the

bouncer’s role at a famous inn in Vienna.

And off Duffy goes on a trek through the Alps. All manner of strange monsters and beasts

slipping in and out of the mist, he also makes a few friends along the

way. Arriving at the inn, however,

things turn really mysterious.

Hallucinations, Vikings from centuries past, and ghosts deep in the

cellars shake the metaphysical realities of Duffy’s world. And he needs to get things sorted out fast;

the threat of war is arising from the west, all things seem to be centered on

his inn, and for some reason, the special brew fermenting deep below ground.

Monday, February 8, 2016

Review of Crompton Divided by Robert Sheckley

For

a while I’ve been meaning to write an essay about the real ‘big three’ of the

Silver Age. Arthur C. Clarke’s existence

unredoubtable, I strongly question Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov’s positions

in the triumvirate, however. If

popularity is the stick of measure, then I have no argument. But if quality of prose, depth of concept,

and underlying humanism are at stake, Algis Budrys and Robert Sheckley should

be in the spotlight. While only a light

example why, Sheckley’s 1978 Crompton

Divided (aka The Alchemical Marriage

of Alistair Crompton) nevertheless possesses qualities that engage deeper

levels of the brain than the works of Heinie or Azzie.

Channeling

dynamic, vibrant prose a la Alfred

Bester with a twist of wit, Crompton

Divided tells the life travails of one Alistair Crompton. His personality recognized as dangerous as a

child, two pieces of his personality are cut out and distributed into android

minds, leaving the real Crompton a cold, placid machine of a human. Growing up to become the top creator of

psychosmells (odors that touch the lizard brain in unique, pleasurable ways)

for the universe’s most successful corporation, he grows bored being the best,

and one day decides to reintegrate his personality pieces. The doctor who

performed the surgery when he was young unwilling to undo his work,

nevertheless gives Crompton the names and locations of the androids who have

his lost parts. Crompton’s quest is soon underway, but it ends sooner than

he—and the reader—expect.

Sunday, February 7, 2016

Review of The Great Wheel by Ian R. Macleod

Toward

the end of Brian Aldiss’ Helliconia Winter, the main character escapes

certain punishment for murder by entering the Wheel of Kharnabar. A massive, single gear turning underground,

it has only one entrance/exit. People

who enter the Wheel must wait ten years for one revolution of the gear to bring

them back to the entrance again. A decade

a long time, the experience brings the novel’s protagonist into a different

plane of mind that, once he exits, allows him to live his life with new

focus. Less planetary adventure and more

near-future noir, Ian Macleod’s debut novel The

Great Wheel (1997) works with similar symbolism to bring about personal

resolution involving the guilt of living in post-colonial Europe.

When

guilt is a key subject, no better main character may be than a priest. In The

Great Wheel his name is John, and he has been assigned by the presbytery in

England for a year to the Endless City, a third-world ghetto sprawling along

the north coast of Africa. A European

and therefore privileged, John receives medical treatments protecting him

against the variety of diseases and ailments that riddle the people who come to

his church seeking help. Seeing the

suffering and waste on a daily basis, the simple medicines John dispenses do

not have a larger effect, and so when noticing a pattern in the symptoms

suffered by people who chew a narcotic leaf called koiyl, he begins to dig further.

Meeting a local named Laura, the two travel into the wastelands of

Africa trying to get to the source of the contaminated koiyl. Though the locals

cast a wary eye on the pair as they travel, it’s after their return, however,

that the troubles of John’s life come crashing down and the circumstances

become too big to handle. Or at least

John perceives…

Friday, February 5, 2016

Review of The Extremes by Christopher Priest

In

social work, there is much made of the enabler—the person who wittingly or

unwittingly aids another’s self-destruction.

C’mon John, just one more

drink... Sure, we can wallow in your

mother’s death for the thousandth time, just tell me what makes you sad… Yes, it makes sense Sally; he shows his love

by beating you… And on and on go the

scenarios wherein friends may actually be more hurtful than helpful. But what about when the ‘friend’ is

technology? Christopher Priest’s late

entry to cyberpunk, The Extremes

(1998), is one such resonant tale.

But

before jumping into The Extremes, we

should back up a little. Priest’s fourth novel, A Dream of Wessex, featured a young woman attempting to deal with

personal issues by getting involved with a virtual reality project. Manipulated, the choice turned out to be

something quite horrific in the end, an experience much more than she expected. Apparently not satisfied with the outcome,

Priest revisited the premise in The

Extremes.

Wednesday, February 3, 2016

Review of The Empire of Ice Cream: Stories by Jeffrey Ford

Emerging

in the late morning of an overcast day (one novel in 1988 and a handful of

short stories over the decade that followed), there was not much indication

Jeffrey Ford would become as prolific as he has. In 1997 he produced The Well-Built City

trilogy which did well critically, but was not a commercial success. A deluge of short fiction followed, however,

and since 2000 he has produced more than ninety stories amidst a couple of

novels. Quantity and quality often

quarrelsome bedfellows, Ford proves harmony is possible, a fact wonderfully

exemplified by his second collection The

Empire of Ice Cream: Stories (2006).

What else do you want on a warm, sunny afternoon?

The

best of the second quarter of Ford’s oeuvre to date, The Empire of Ice Cream: Stories contains a wide range of tales,

all written in attentive, quality prose.

While style varies only slightly to accommodate the story being told, the

subject matter broached is far-ranging.

Faery, explorations of the act of writing, Americana, synesthesia,

dreams, (superb) barroom storytelling, Weird, the mythological, tall tales,

folk tales, dark fantasy—the stories are rooted in a wide variety of modes and

moods, which make the collection all the more satisfying.

Monday, February 1, 2016

Review of Howl's Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones

There

are times that you encounter such a charming, delightful book that you only

realize it after finding your head floating in the clouds. Colorful, imaginative, fun, layered, unique,

pitch perfect prose—these are some the main attributes you look back upon

having drifted away. One such story must

certainly be one of the most immersive fantasy novels of all time, Diana Wynne

Jones’ superb Howl’s Moving Castle

(1986).

Distilling

the pure essence of fairy tale and creating a sub-text involving relationships,

gender, and maturation in a contemporary storyline, Howl’s Moving Castle is a novel that perfectly straddles the fence

between modern and traditional with nothing lost between. Borrowing the best of both worlds, there are

wizards and witches, spells and magic, but these familiar devices are deployed

in a story that transcends even the notion of stereotype. Howl is a young wizard of extraordinary

talents, but prone to wallowing in self-pity.

Sophie is a quiet, unconfident young woman who feels herself trapped to

one path in life, unable to escape while those around her have all the

fun. And the Witch of the Waste, well,

she just might be as classic as evil in fairy tales gets. But I get ahead of myself.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)