Catchpenny is the story of one Sid Catchpenny. A former singer turned thief, in the opening pages he is looking for something genuine to do with his pathetic, plastic life; his doppelganger murdered his wife years ago and his career as a performer was traded away in a deal with a devil, meaning he spends his days wallowing in cheap self-pity. That is, until one day when a taxi-driving friend asks Sid to pay a visit to someone and get some information, some character information that will help the driver sort out a little domestic trouble he's having. And down the rabbit hole Sid unwittingly goes. Gangsters, mojo, influencers, mannequins, D&D, cults, and weird video games form a carousel, a carousel that spins ever faster with each new encounter. Trouble is, how to stop the ride?

Monday, May 27, 2024

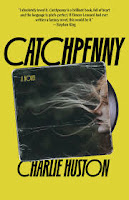

Review of Catchpenny by Charlie Huston

Review of Tallarn by John French

Covering the spectrum of story length, Tallarn contains four pieces: one bit of flash fiction, one short story, one novella, and one novel. Presented chronologically, they describe the Iron Warriors surprise attack, the locals' resistance, and Peturabo's ultimate purpose taking the planet. Like Corax, the stories form a chain telling an overarching story. A more interesting mix, however, it proves to be one of the better collections/anthologies in the Horus Heresy.

Wednesday, May 22, 2024

Review of Gardens of the Moon by Steven Erikson

Gardens of the Moon tells of the ambitious empress of the Malazan empire, Laseen, and her ruthless campaign to conquer the continent of Genabackis. The jewel of Genebackis is the neon blue-green city of Darujhistan. After taking the neighboring city of Pale, its there Laseen sets her sights, with the Bridgeburner brigade, and its collection of colorful soldiers, at the vanguard. Opposing the Empress is Anomander Rake, the eternal Tiste Andii lord of Moon's Spawn, a massive rock island that floats above Genabackis. At his beck and call are armies of large ravens and mage-assassins, entities Rake deploys to carry out his own mysterious plans.

Saturday, May 18, 2024

Review of The Tusks of Extinction by Ray Nayler

The Tusks of Extinction is set in a near future in which DNA can be used to bring extinct animals back into existence. Mammoths have been recreated and raised in numbers high enough to re-populate the Russian steppe. In tow have come poachers, men who hunt the massive animals for their tusks, as well as trophy hunters, billionaires looking to take down one of the large males for a wall decoration. Angry at these killings, a group of scientists decide to input the mind of one of their own into a mammoth to give the massive beasts a chance at survival.

Wednesday, May 15, 2024

Non-fiction: Review of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt

I am Gen X. I know what it's like to have a land-line telephone in the house. I had thousands of negotiations with my teen sister, who gets to use that phone and when. And nowadays, I know what's it's like to have a smartphone, to be able to connect any time, almost anywhere—not only to a person, but to the collection of human knowledge and advertizement, for better and worse. But my two children, 7 and 9, don't have this perspective. They know only a smartphone world. And they are the first generation to have such a perspective—the guinea pigs of the human race. Jonathan Haidt, in his 2024 book The Anxious Generation, asks us to take a closer look at the experiment.

The trigger for The Anxious Generation were the spikes in teen anxiety and depression Haidt and his team observed post-2009/2010 til now. Looking deeper into the data, Haidt, a social psychologist, was particularly interested in identifying the potential causes. After all, nobody wants the future leaders of the world to enter adulthood with significantly higher chances of depression.

Friday, May 10, 2024

Review of Praetorian of Dorn by John French

Rogal Dorn is a primarch situated on Terra, a planet far from the loyalist vs. traitor battlefields happening across the universe as Horus attempts to take over the Imperium. He and his Imperial Fists are preparing defences, knowing Horus is coming. But as with any large scale assault, Horus knows shaping operations are necessary. Praetorian of Dorn by John French (2016) are precisely those operations.

In military parlance, shaping operations are covert military operations intended to destabilize defenders before a major frontal assault is launched. Typically performed by special ops, it's appropriate the Alpha Legion, led by its enigmatic primarch Alpharius, are the team sent secretly in to Sol to “soften the ground” at the outset of Praetorian of Dorn. Undercover agents appearing in the most unlikely of places with powerful psyker mind games being played internally and externally, the novel quickly escalates, turns on a dozen dimes, and still has room for surprise at the conclusion. The novel is a bit of controlled chaos, exactly as operations shaping Horus's assualt on Terra should be.

Review of Scars by Chris Wraight

I'm almost at the Siege of Terra. But before cracking the first of those ten books, I promised myself I would read at least one Horus Heresy book per Legion. Some Legions have featured prominently in several books—Sons of Horus, Ultramarines, Emperor's Children, Death Angels, Blood Angels, etc. But some make minimal appearances. Legion, for example, is the only novel (to my knowledge) to focus on the Alpha Legion. And here there is Scars (2013), the 28th book book in the series, which focuses on one of the other aloof legions, the White Scars.

Scars centers on the primarch Jagatai Khan's legion and their journey from outliers to participants in the Heresy. Living distantly, far from the events of Isstvan and beyond, their creed has kept them out of the battles engulfing the human species. The events of Prospero, however, prove to be the catalyst bringing the Scars into the picture. With reports of brother attacking brother, Jagatai cautiously boards his ships and heads out to find out precisely what happened between Leman Russ and Magnus the Red, and in the process must do the last thing he expected, or wants to do: choose sides.

Monday, May 6, 2024

Review of Expect Me Tomorrow by Christopher Priest

Most avid readers have their favorite authors, and 2024 has been been merciful to a few of mine. Terry Bisson and Howard Waldrop both passed away, taking with them unique, meaningful voices of speculative fiction. And the year likewise took Christopher Priest, a giant in the field. A book published just two years ago, Expect Me Tomorrow (2022).

Expect Me Tomorrow rotates through three time periods/perspectives, steadily revealing the relationship between them. Told in brief, dry snippets akin to a history book, the first perspective is the story of a Victorian confidence trickster named John Smith who was found guilty of cheating women out of their valuables. The second is told in a warm, first-person perspective with a classic English lilt. It tells of a pair of Norwegian twins in the mid 19th century, Adolph and Adler. Night and day in terms of career interests, Adler is an academic researcher interested in climate who ends up spending many years in the US pursuing knowledge while his brother Adolph is an opera singer who tours South America. And the third perspective is an alternate take on our modern times, written in Priest's precise prose, in which a police profiler has a piece of network tech installed in his head giving him direct access to the internet. Disparate stories at the outset, Priest slowly weaves these three into a single tale.