Pablo

Picasso had his “blue period,” Max Ernst his “American years,” and Georgia

O’Keeffe her later “door-in-adobe” phase.

For J.G. Ballard, the early part of his career could be called his

“psychological catastrophe years.” Using

environmental disaster as a doorway to viewing minds under duress, novels like The Drowned World, The Drought, and The Crystal World unpacked the underlying subject matter. For the next phase of his career, Ballard

moved into the world of celebrity, media, violence, sexuality, and how they

distort and are distorted by reality.

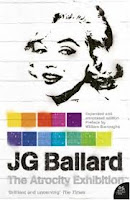

Like any good artist, Ballard produced preliminary sketches prior to

delving into the longer length works of Crash,

Concrete Island, and High-Rise. Arguably as experimental as literature can

be, this initial feeling-out of mass media’s effect on the individual is 1970’s

The Atrocity Exhibition.

A

collage of Marilyn Monroe, fast cars, Vietnam War imagery, pornography, and

numerous other symbols of the 60s shredded into bits and pasted randomly back

together, The Atrocity Exhibition is

as much art as literature. Presentation literally mimicking a gallery

exhibition (i.e. the ability to walk in and let your gaze fall where it will),

readers looking for traditional storytelling should run. Like a later novel The Unlimited Dream Company, Ballard presents the same variety of

images, symbols, and conceptions from different angles, forcing the reader to

take a step back to view the larger whole.

There are thus recurring characters, but it is not their story, rather

the multi-perspective view to their experiences which address Ballard’s

concerns.

Normally

the writer places each word on the page with the intention it will be

read. The Atrocity Exhibition abandons this philosophy. In the introduction, Ballard encourages the

reader to dabble, to dip in and out, to get the flavor of the whole by sampling

randomly. The wall of scenes in the

gallery is to be observed. Most of the

artistic elements are common yet differ in array individually, and from that

the reader can draw their own conclusions .

If you are not a lover of visual art, then this aspect of the book can

be difficult to appreciate. As it’s the

main mode of presentation, I would even go so far to say that if the idea

doesn’t interest, don’t read the book.

Tolerances of the Human Face in Crash Impacts. Travers took the glass of whisky from Karen

Novotny. 'Who is Koester?—the crash on the motorway was a decoy. Half the time

we're moving about in other people's games.' He followed her on to the balcony.

The evening traffic turned along the outer circle of the park. The past few

days had formed a pleasant no-man's land, a dead zone on the clock. As she took

his arm in a domestic gesture he looked at her for the first time in half an

hour. This strange young woman, moving in a complex of undefined roles, the gun

moll of intellectual hoodlums with her art critical jargon and bizarre magazine

subscriptions. He had met her in the demonstration cinema during the interval,

immediately aware that she would form the perfect subject for the re-enactment

he had conceived. What were she and her fey crowd doing at a conference on

facial surgery? No doubt the lectures were listed in the diary pages of Vogue, with the

professors of tropical diseases as popular with their claques as fashionable

hairdressers. 'What about you, Karen?—wouldn't you like to be in the movies?'

With a stiff forefinger she explored the knuckle of his wrist. 'We're all in

the movies.'

A

novel only in the loosest sense possible, The

Atrocity Exhibition plays with structure, semiography, and semantics to

create ideas in the reader’s mind, that is, rather than convey ideas via

story. The true definition of a ‘mosaic

novel,’ Ballard examines the intersection of commercial art and reality, media

and the lives it presents, people who consume media, their perception of

reality, and the twisted reality of those in media. Fully focused on the effects of Vietnam-era

media on society, an absurdly extreme view is presented in the hope of exposing

some of the deeper paradigms at play in humanity—much like his earlier

‘psychological catastrophe’ novels, but with a deeper view to the interaction

of society and media. “World War III is now little more than a

sinister pop art display”one of the characters boldly states at one point.

The

version I read containing Ballard’s own chapter annotations, one finds such

quotes as: “a kind of banalization of

celebrity has occurred: we are now offered an instant, ready-to-mix fame as

nutritious as packet soup.” And that was in 1970. With the popularity of “reality tv” in

contemporary society, among several other things, one has to view The Atrocity Exhibition as a significant artistic statement regarding the surrounding human phenomena. The array of vignettes fascinating for their

imagery alone, pondering their significance in context with the whole makes for

fascinating, disturbing, and informative reading—one of the highest compliments

one can pay a piece of writing.

No comments:

Post a Comment